Islamic philanthropy: Waqf

During the WIEF Roundtable in 2015, leaders of waqf institutions and various governing bodies discussed the key measures needed for waqf to facilitate socioeconomic development.

Waqf comes in many forms: direct forms of assets donated to fulfil a community needs; investment waqf where earnings are used for the benefit of specific communities; religious waqf for schools and mosques; philanthropic waqf to address the social needs of the poor and underprivileged; family waqf where descendants of the waqf have first rights to receive the benefits and revenues of the waqf; and Irsad which is an endowment by a sovereign for designated beneficiaries.

Dr H. M. Anwar Ibrahim, Head of the Executive Council of Indonesian Waqf Board, strongly believed that waqf could play important roles in social development, as well as in the building of an economy. While presenting an overview of the waqf landscape in Indonesia, Dr Anwar said, despite being the world’s largest Muslim country and considerably rich in waqf assets, Indonesia’s waqf system was rather underdeveloped.

As such, Dr Anwar offered three key measures: first, the benefits of waqf must be inculcated in the society; second, we must continue to promote and integrate waqf into our economic agenda; and lastly, waqf study must be introduced in tertiary education.

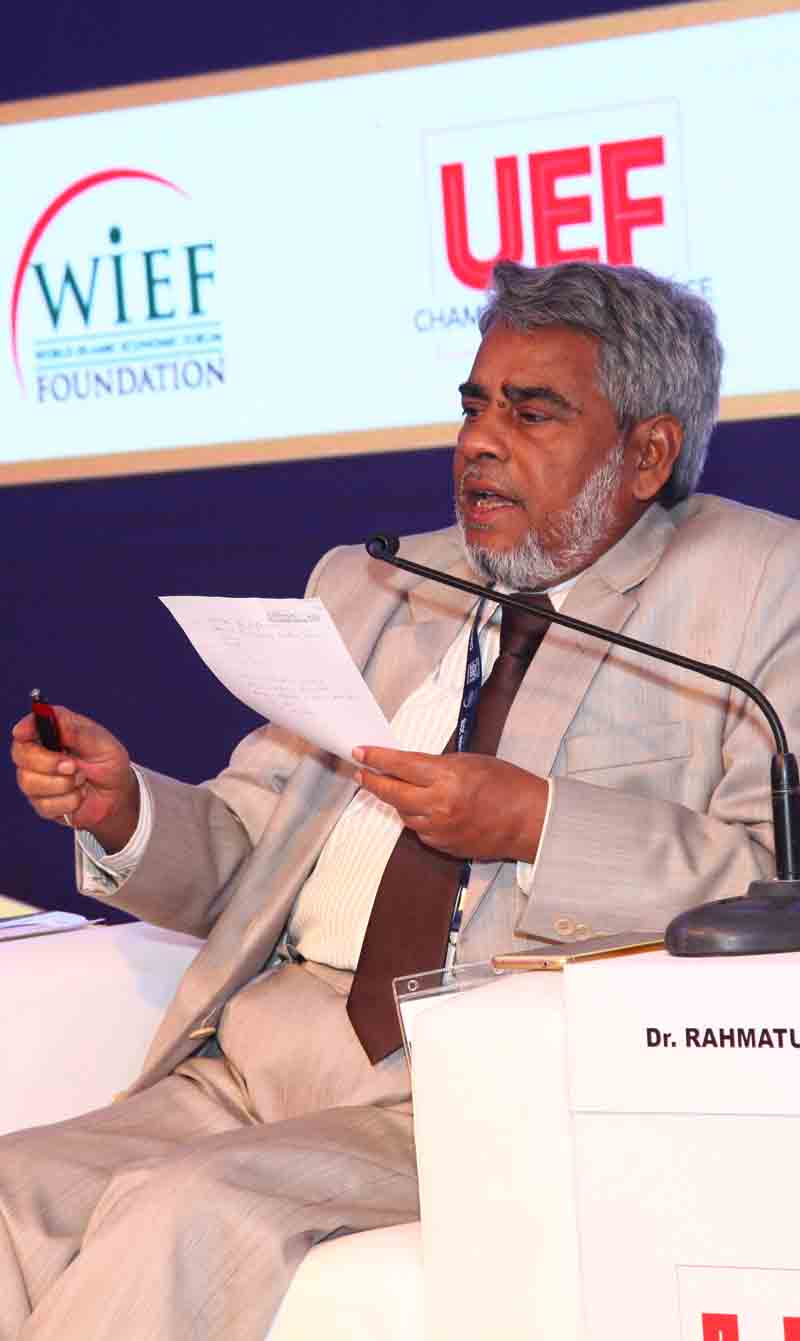

Professor Datuk Dr Mohd Azmi Omar, Director-General, Islamic Research and Training Institute, Islamic Development Bank Group (IDBG) agreed with Dr Anwar that waqf is not only instrumental for poverty alleviation but also in economic growth.

In his presentation, Professor Azmi focused on the need for new and innovative waqf products and approaches, such as using other financing instruments to implement microfinance. ‘Cash waqf can be used for microfinance activities and, at the same time, zakat and sadaqah are used to provide technical assistance, such as skills-training, to the borrowers. In this way microfinancing and capacity-building are provided simultaneously,’ he explained.

‘Furthermore, to address the issue of depletion of the waqf fund, group members are encouraged to form a takaful fund to provide micro-insurance against unforeseen risks and uncertainties resulting in loss of livelihood, sickness and so on,’ he added. Noting that the IDBG has implemented several programmes integrating philanthropy with microfinance, including the Deprived Families Empowerment Programme in Palestine and the Fa’el Khair Programme in Bangladesh, Professor Azmi said there were several lessons that could be learned.

Dr H. M. Anwar Ibrahim, Head of the Executive Council of Indonesian Waqf Board, urged for more efforts to be invested in developing the waqf system in Indonesia learnt from these pilot projects: ‘First, we need to have a good regulatory framework, which must seek to strike a balance between concerns about preservation and development.’

He also observed that waqf law should provide a comprehensive definition of waqf that included both permanent and temporary waqf. ‘The legal framework must clearly articulate the permanent nature of waqf arising from the principle of ‘once a waqf, always a waqf’,’ he said, remarking that there was a tendency for certain governments to utilise awqaf without replacing them.

Professor Azmi also suggested that waqf be incentivised in a manner similar to secular trusts and other not-for-profit instruments. ‘For instance, providing tax rebates for the donor or endower on contributions would make the system both efficient and fair,’ he explained.

Another lesson learnt was that the legal framework should not restrict making a waqf available only to Muslim individuals, and the definition of the endowed asset should not be restricted to immovable tangible assets, such as real estate, but should also explicitly recognise movable, financial and intangible assets.

As for the question of whether awqaf should be placed under state or individual ownership, Professor Azmi admitted that there was no clear- cut answer. ‘Waqf is originally an institution and is always meant to be in the voluntary sector with management of the waqf entrusted to private parties. At the end of the day, it depends on the professional management and the regulatory framework. If it is under private ownership, then clear-cut KPIs and performance evaluation must be put in place in order to ensure that the waqf is really managed according to the terms and conditions,’ he stressed. Professor Azmi reiterated the importance of not relying on waqf alone to alleviate poverty but combining it with zakat, sadaqah and Islamic microfinance.

Wrapping up the session, moderator Zeinoul Abedien Cajee, Founding CEO of Awqaf South Africa, proposed that the waqf system be reverted to civil society, as civil society was originally the main driver of the system when it started in Medina.

Management challenges and waqf assets

Whereas the previous session examined the enormous potential of waqf assets in developing

the economy and alleviating poverty, this session explored the practicalities of managing those assets.

One model, presented by Tan Sri Muhammad Ali Hashim, former President of the Malaysian Islamic Chamber of Commerce, was ‘corporate waqf’. He described corporate waqf as a tool of ‘business jihad’, a phrase he coined to articulate the key ideological strategy in the struggle for Islamic economic transformation.

‘Corporations rule the world today, with most of the highly valuable assets in their hands,’ he said, but with the rich getting richer and private sector interests crowding out the people’s interests, this has created severe global problems.

‘The divide between the rich and the poor is expanding all over the world, and there is no solution from the Western capitalist side. The Wall Street culture is damaging societies everywhere…more so in Muslim countries, because Muslim countries are more sensitive towards inequality.’

Muhammad Ali proposed that the Muslim world address this problem through corporate waqf, explaining that the agenda of corporate waqf was to reform capitalism by shifting away from the dominant shareholder-centric system to a community-centric system.

He shared his experiences in Johor Corporation (JCorp) in Malaysia (of which he was former President and CEO), which had undertaken the major process of converting its billion-ringgit assets into waqf. As a government-linked corporation with a market capitalisation of about USD7 billion, JCorp had to strike a balance between profit-making and social responsibility, and it identified several management challenges to be addressed in the practice of corporate waqf.

‘For waqf, you hand over the ownership to Allah, so you need to have established the ownership structure for the practical management of the assets,’ he said.

A business-driven waqf entity also had to redefine the entrepreneurship platform and convert the system from an owner-driven business to a waqf-driven system; and here Muhammad Ali referred to the waqf manager as an “intrapreneur”, that is, one who did not own the business but still had to deliver in terms of business objectives.

He explained that the concept of waqf intrapreneur or ‘amanah entrepreneur’ also allowed young Muslim entrepreneurs to access business opportunities that might otherwise be denied in the mainstream (and more exclusive) corporate world.

Apart from corporate waqf, another model that could promote the use of waqf assets was ’waqf engineering’. Husain Benyounis, Secretary-General of Awqaf New Zealand, elaborated on the model that his organisation had developed, called World Awqaf Qard Fund Services (WAQF-S), which sought to bridge the gap between the profit and non-profit sectors.

‘To turn wasted charitable resources into waqf revenue, we established waqf farms for livestock to supply five million sheep a year for the qurbani industry for Muslims in the West,’ Husain explained.

‘WAQF-S will not only bridge the gap between the banking and non-banking sectors of the Islamic economy, it will also help to balance the Islamic economy, enhance the efficiency of the non- profit sector and revive the sunnah of qard al-hassan,’ he added.

WAQF-S also develops new Islamic finance tools for the non-profit sector, provides secured infrastructure to globalise the waqf industry, and ensures a high degree of transparency via waqf sukuk.

Husain was confident that this model would be able to help overcome management challenges of waqf assets, such as taxation, cross-border relations, transparency, efficiency and shariah compliance.

___________________

This report is based on a WIEF Roundtable discussion in 2015.

Photo Credit: Jason Cooper