Disappearing sculptures

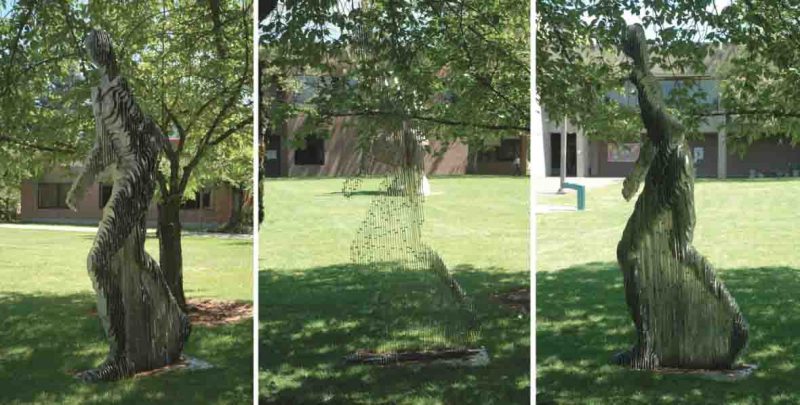

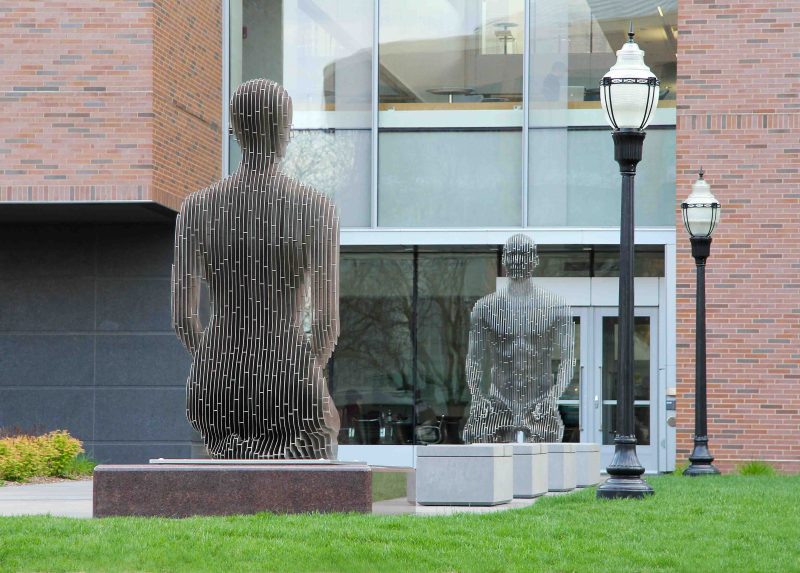

A German-American sculptor famous for his disappearing sculptures made his creations stand out in a unique blend of art, science and technology.

Before he ventured into the science and physics of sculpting, Julian Voss-Andreae explored his passion for arts as a teenager. However, that teenage phase didn’t last. ‘I would copy the 2D appearance of the 3D world onto my paper at the same scale it appeared to my eye. Then I took some drawing classes and received the message that my approach was all wrong,’ he said. The process of learning how to draw confused him and paused him from pursuing a career in art altogether until he ventured into physics.

His interest in physics started with a book he read, called The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds and The Laws of Physics by Roger Penrose, which sparked his curiosity about quantum physics. That led him to study physics. He also went on to explore more about the correlation between art and science after his poet friend insisted on their happy coexistence.

During his graduate study at the University of Berlin in 1999, Julian attended a workshop in Italy designed for natural scientists to go beyond the usual confines of scientific work like art, psychology and other systems of traditional spirituality. That’s when he made his first ever sculpture, a totem-like self-portrait carved out of wood.

The DNA of his art

By then, Julian had acquired skills in physics, most importantly hands-on manipulation of matter, computer programming and general problem-solving abilities which came in very handy for making sculptures. ‘Besides those skills, it’s really my first-hand experience of the enigmatic nature of reality that provided me with key cultural insights, informing my path ever since,’ he said.

After his physics degree, he enrolled in an art college and one of his first assignments was to create a mitre cut sculpture. He cut a piece of square lumber along arbitrary angles, flipped every other part and glued it back together, turning the straight piece of lumber into a line zigzagging through space.

He then recalled a globular protein which is a single strand crumpled into a tight ball and realised that’s what he had done. He did what Mother Nature does when she goes from DNA, a 1D strand of information, to 3D bodies.

Julian’s imagination set him out to write a computer programme that would turn structural protein data into cutting instructions to make mitre cut protein sculptures. His first ever sculpture project was to make a green fluorescent protein structure, a protein that makes certain jellyfish glow green in the dark.

‘I started out using mostly mitre cuts on a variety of materials, like lumber, bamboo, and whole trees,’ Julian explained. He then took up welding, using steel beams and a lot of laser-cut steel sheets to create works that would better hold up against gravity.

With the recent availability of 3D printing, he got adventurous and created a new type of sculpture. ‘I used a lot of 3D printing, typically direct casting the printed parts in bronze. We did most of the bronze fabrication in my shop and I used glass from sheets, water-jet cut or cut by hand, sometimes kiln-formed. Recently, I started using titanium for the first time,’ he said.

Technology behind it

Julian used a mix of often old and easily available software and technologies that helped him in designs, he even wrote some software himself. ‘Some software I wrote myself or I commissioned custom-written plug-ins for existing software to solve special problems. I tend to do specific things with certain pieces of software.

‘It’s probably the nature of my work that no one programme alone could do all the things I wanted. I typically worked with two computers running at the same time since many processes are pretty time-consuming. In addition to 3D printing, I frequently used 3D scanning as a starting point for my designs. I also used a number of different 3D scanning technologies depending on what I needed and built a large 3D scan rig in my studio that contained 166 small computers with cameras,’ he explained.

Among his many treasured sculptures is his Quantum Man, his first disappearing break-through piece in 2006 and his recent Analysed Odalisque, a reclining woman in stainless steel slices that used the direction of the gaze as the disappearing angle.

Future creations

His most recent art projects involved three large public works. One was installed earlier this year [2018] in Palm Springs, California. It included a lot of LED coloured lighting which he programmed, adding a new layer to his work. ‘In addition to that, we’re working on a bronze piece that will have lights inside. We’re also in the process of figuring out how to work with titanium for a new, really cool piece. I’m also exploring the feasibility of a large project that involves decorating a very large façade of a huge building. That’s a complete departure from sculptures and goes back to my 2D graphics interest.’ he said.

Julian felt very much like he was pursuing some kind of research programme, throughout these years. ‘I had a vision of what I wanted and I pursued it slowly but surely, often over many years, until I was there. On the path towards realisation, many projects spun off,’ he said.

He advised young artists not to be discouraged in this world. ‘Don’t let the art world drive you crazy. There are always plenty of disappointments and rejections you’ll have to learn to live with until it stops and it might never stop,’ he advised. To avoid dwelling on these disappointments, he said an artist should have enough things to excite him/her to keep going. ‘Stay true to your passion and vision even if you can’t explain why you do it. Ultimately, the point of art is something that’s beyond words,’ he concluded.

___________________