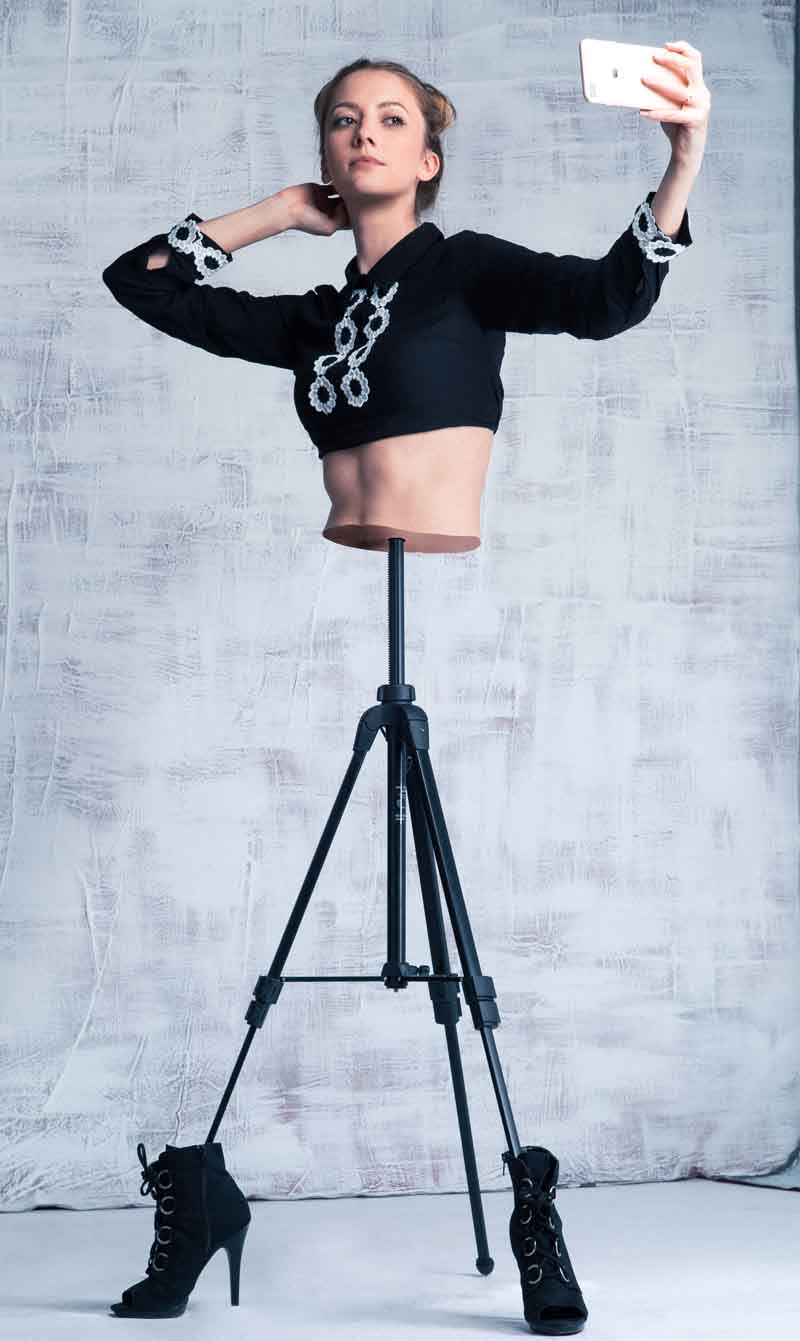

Plastic you can drink

CEO of Avani bags believes we can really stop using plastic. He discusses how the bioplastic bag may be the best alternative, also about the thing he calls cassabag and the fact that it’s edible.

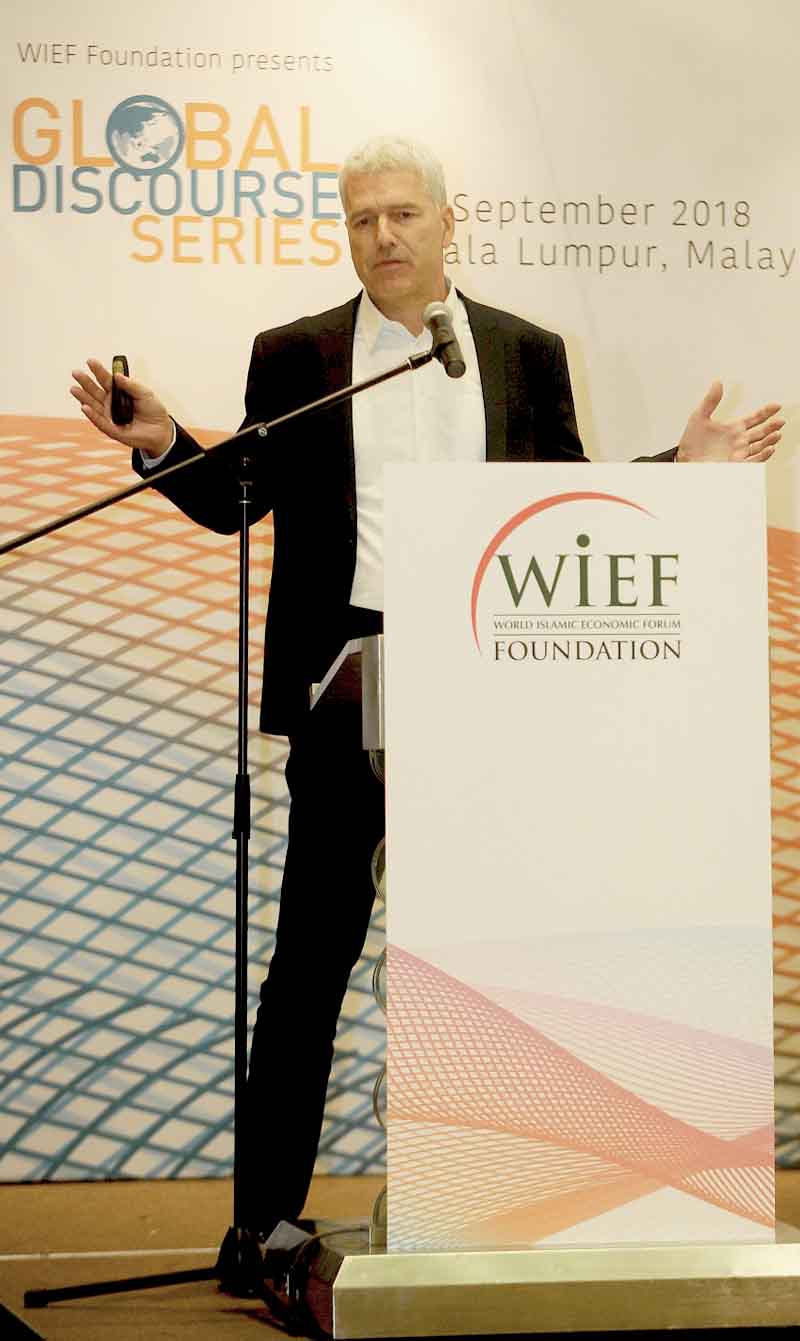

Plastic bags that aren’t really plastic are being made in Bali, Indonesia, by 33-year-old founder and CEO of Avani, Kevin Kumala. With a bachelor’s degree in biological sciences, he used his two years’ worth of research on a feasibility study to solve the growing environmental issue of plastic pollution. Kevin and his team used to call Avani bags ‘cassabag’ because they were made of cassava starch, making it edible and safe to consume.

The Avani project was like a calling for Kevin. He said his passion for environmentalism was due to his surfing and diving hobbies that raised his environmental awareness. Backed by his educational background and business management skills, he set up Avani in 2014, a bio-based solution and alternative to plastic.

After completing his studies in 2009 in the United States, he returned to his home in Indonesia to help with his family’s business. He later decided to venture into his own business, Avani, by setting up an algae harvesting farm in Jakarta. Algae was just one of the feedstocks used in the bioplastics industry.

How it’s made

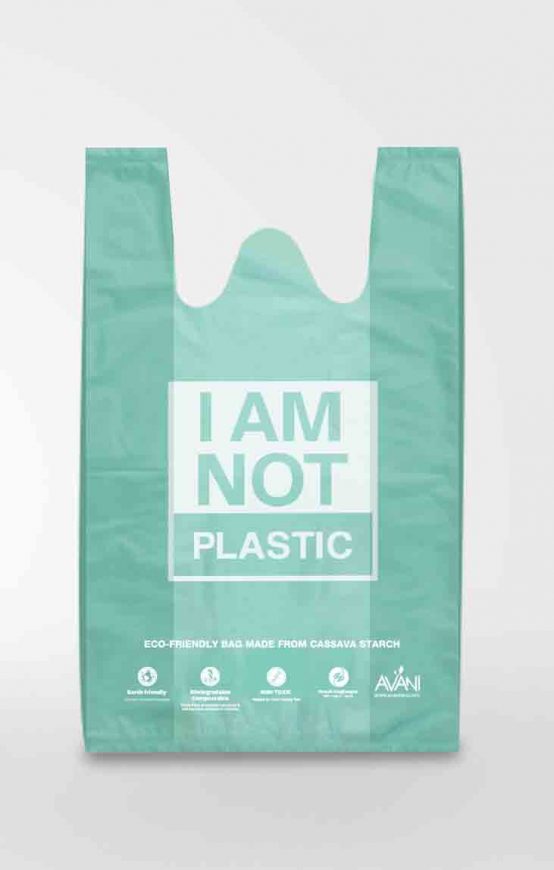

Being located in Indonesia gave Avani access to an abundance of waste materials derived from biomass. All Avani products were made entirely of renewable resources and non-petroleum-based materials, so they weren’t using any non-renewable energy sources. The materials used for Avani bags were derived primarily from industrial grade cassava starch, derivatives of vegetable oil and other natural ingredients. With those materials, Avani didn’t require a special commercial composting facility to become compost for the environment. The bags are biodegradable and can even be dissolved in hot water. At many events, Kevin had demonstrated tearing the cassava bag into lukewarm water which immediately diluted it, making it safe and ready for drinking.

It also passed the oral toxicity testing to certify that the bags were safe enough for animals to eat. Other regular testings were conducted in the Avani factory and office to constantly obtain the highest level of composability endorsed by international standards. ‘In terms of scalability, it’s also very advantageous due to the abundance of cassava, yucca and potato which could be utilised in our expansion to other countries in the future. By utilising economical raw materials, Avani has proven to be one of the most economical compostable bags available in the marketplace today,’ Kevin said.

Industry giants such as Unilever have also sought out Avani as a sustainable business practice. ‘Being able to work with Indonesia’s leading hotel chain, Archipelago International and other multinational companies such as Motul, have been exciting as well as memorable moments for us as a team,’ he said

Location is everything

Bali’s location as a tourist melting pot also helped Avani to market itself to people from all over the world. Avani’s walking billboards and products were easily exposed and picked up by different island visitors. ‘We’re fortunate that the plastic problem lies very close to the eyes of the people living on this island. With that said, the snowball effect happened quickly as customers automatically became our brand evangelists. They would actually be the first ones to bring the products and market them through word of mouth,’ he said.

Although their focus lied on their primary target market which was the hospitality sector, they’ve also branched out to serve retail, packaging and even medical industries. Kevin saw that their customer base would inevitably grow since plastic was used in almost every industry. Currently, Avani has distributors serving five parts of the world including the United Arab Emirates, CARICOM countries, Singapore, Turkey and Romania.

What about regular plastic?

Though Avani bags were better alternatives to plastic bags, Kevin said they couldn’t be compared with regular plastic due to their economy of scale and commodity items being used. ‘Generally speaking, Avani products cost 30 to 200 per cent more, compared to regular plastic. We’re hoping the market absorbance will eventually help us gain this economy of scale and enable us to offer our products more economically in the future,’ Kevin said.

Kevin said they often referred to their plastic bags as cassava bag or cassabag but because of other counterfeit items and their non-recyclable nature, they resolved to commonly refer to them as bioplastic.

Despite his strong environmental beliefs and with the introduction of Avani, Kevin still didn’t think plastic bags would cease to exist. ‘Plastic is lightweight, convenient and durable. However, I do believe that the reliance and usage of plastic will definitely decrease as years go by,’ he said. Many countries have implemented some sort of control in plastic consumption, thanks to independent researchers who have also served as a great awakening.

Last words

Kevin envisioned a perfect utopia in which there would be no plastic bags. He understood, however, that it would take much more to change consumer behaviour and habits which involved education, an improvement in infrastructure and waste management. ‘[These] are complicated networks which should be synergised in order for this utopia to happen,’ he said.

He hoped to develop more alternatives to plastic products derived from waste and turn them into things of value. ‘We’d like to develop eco-friendly products which are not only disposable but reusable and recyclable. Our vision is to be able to turn waste into compostable products,’ he concluded.