The Little Newsletter that Could

Turning a magazine around and making it a go-to source of information takes a bold attitude with a heavy dose of fervour which Pim Kemasingki has in spades. Sehra Yeap chats with her in Chiang Mai to unfold her uncommon entrepreneurial tale. This was published in the first edition of In Focus.

Pim Kemasingki grew up in a life of relative comfort and privilege, like many girls born into the upper strata of Thai society. Her English father, John Shaw MBE, was the British Honorary Consul to Chiang Mai. Her mother Pat Kemasingki was the daughter of a high-ranking Thai army officer who, before allowing the Englishman to marry his daughter, had sent his staff to Oxford to investigate whether the young man’s claim of having received his master’s degree in Modern History from Magdalen College was, indeed, true. (It was.)

Pim, their only child, was born in the early 1970s, a luk kreung or ‘half-child’, the Thai term for a child of mixed parentage. She spent her childhood years variously in Thailand, Indonesia and Hong Kong, went to high school in Switzerland and thereafter attended Aberdeen University in Scotland, where she graduated with a master’s degree in English literature.

At birth, she was named Pim Shaw, but in 1998, when she took over as managing editor of Trisila Company Limited, the publishing company founded by her father, she decided to use her mother’s Thai maiden name, Pim.

‘I knew that I was going to be writing about Thailand and that it wouldn’t always be complimentary. I figured, correctly as it turns out, that I could get away with saying a lot more about this country as a Thai,’ she says. Like her father before her, Pim doesn’t shy away from commenting on issues in a country where sensitivities of rank, social status or political affiliation can sometimes outweigh other considerations.

How it Started

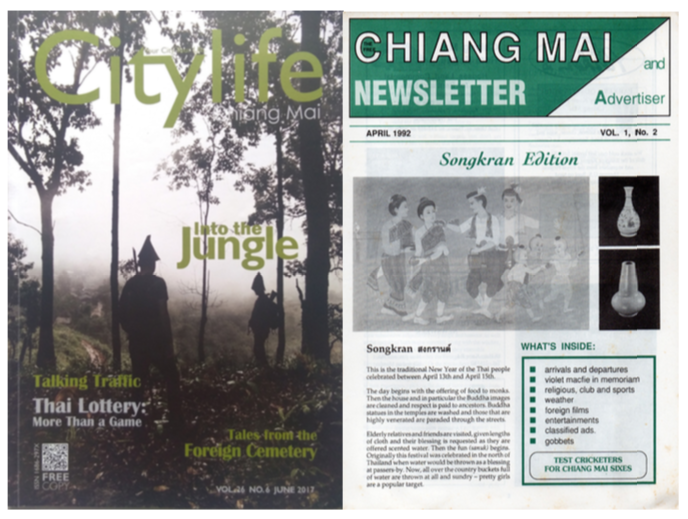

Citylife magazine, the company’s flagship English-language publication, was founded in March 1992 as The Free Chiang Mai Newsletter and Advertiser. It was published by Pim’s father John, together with two other British expatriates, John Hobday and John Cadet. The newsletter was intended to inform expatriates about local events and news, as well as a medium for businesses in Chiang Mai to advertise to the English-speaking community.

The main aim of the newsletter, its founding editors wrote, was ‘to provide the medium through which Chiang Mai can communicate with itself,’ and – before the era of the internet – it was envisaged that it would be ‘a long-term contribution to, and communication with, the multicultural life of the city.’

I had arranged to meet Pim for a coffee in a pleasant, tree-shaded café in the trendy Nimmanhaemin quarter of Chiang Mai. What was Chiang Mai, and the newsletter, like back in the early 1990s? I ask. ‘It was all very charming and the newsletter carried social notices such as “Mr & Mrs so-and-so are setting off on their European tour this summer”,’ she replies.

Originally published on sheets of paper stapled together, The Free Chiang Mai Newsletter was printed in monochrome – single colours were rotated month on month. Its simple format perhaps befitting its early role as a community bulletin in what was once not much more than a provincial town in agrarian northern Thailand.

Despite its long and storied history, Chiang Mai, not far from Thailand’s northern border with Laos and Myanmar, must have once had the air of a sleepy colonial outpost, even if it never was one. The part of Chiang Mai called the ‘old city’ is still enclosed by 19th century fortress walls and a 700-year old moat that was once said to be inhabited by crocodiles.

However, the Chiang Mai of 2017 is a groovy kind of place and teems with artisanal coffee shops that are populated with a hip mix of tourists, fashionable younger Thais and digital nomads. These days it’s the Americans, Australians, Europeans and people from elsewhere in Asia who come to Chiang Mai, giving the place a distinctly international atmosphere.

Even back in the early 1990s, the founding editors of the Chiang Mai Newsletter had already begun addressing issues that concerned the city and its community. In 1993 the Newsletter carried an open letter to the new Chiang Mai Governor. In it, the editors expressed their misgivings, among other things, about Chiang Mai’s new ring road, taxis and tuk-tuks (motorised rickshaws) in the inner city.

The lack of a ‘credible public transport system’ and the great numbers of private vehicles in the inner city which were becoming ‘an increasing problem.’ (Unfortunately, Pim says, this is a problem that Chiang Mai ‘still struggles with’, 20 years on.) The Chiang Mai of the early 1990s was still, wrote John Shaw, ‘a delightfully slow and rustic community’.

Now, however, the words ‘slow’ and ‘rustic’ don’t apply any longer to this city of about one million, with its shiny new mega malls, hotels and condominiums. And it seems that the newsletter has grown apace with the city’s own rapid development in the last two decades.

What it Evolved into

In 2002, 10 years after its founding, The Free Chiang Mai Newsletter was renamed Citylife. The magazine, now a glossy, full- colour monthly periodical, still features articles of social and community interests, happenings in and around Chiang Mai and notices of events. But it’s Pim’s editorial – trenchant and often unflinchingly candid – that has become the barometer of l’air du temps of the city, addressing current issues concerning Chiang Mai and its inhabitants, both local and foreign, as well as the country at large.

She doesn’t shy away from addressing potentially sensitive topics in a country where freedoms of press and expression are still seen as being tightly controlled by the ruling junta. For example, she has lampooned edicts from the Thai Ministry of Culture, which according to her, pushes ‘its mind-bogglingly idiotic attempt to create a master plan for safe and constructive media, which translates to censoring the internet in favour of local – and easily controlled – media’.

In another editorial, in 2014, she confronts an uncomfortable, if little-acknowledged, reality in Thailand, where its tourism industry plays a major contributing role to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP): the ostensible xenophobia of her countrymen. ‘It is, apparently, a privilege to be allowed to step foot into the Kingdom,’ Pim writes of the attitudes of many Thais towards foreigners.

Behind Pim’s pointed admonishments, however, there’s a sense of genuine affection for her city and her people, of a real endeavour to encourage progress in both, using her privilege, as a luk kreung, of having two vantage-points of perspective – even if it means stepping on proverbial toes. It takes rare courage.

Pim also highlights the failings of local authorities to address environmental issues. One of these is Chiang Mai’s yearly smog problem. The high pollution levels in the city caused by farmers in the surrounding areas burning the forests to clear land for planting – as they had done for generations – was hitherto an unaddressed problem.

The smog had become a problem for Chiang Mai city after its rapid expansion in the last 20 years, and someone needed to bring it up. But it was only after an article about the smog, in a 2004 issue of Citylife, that a dialogue could begin about it. ‘You’ve sent a chill down my spine. Everyone talks about Chiang Mai being a hub for this and a hub for that, but it looks as if we can’t even sort out the problem of our most common denominator – air,’ the then-deputy governor of Chiang Mai said of the article.

Thus, in the space of a dozen years or so, the little newsletter for the English-speaking community of Chiang Mai had grown into a voice of social conscience, it seemed, for the city.

The Force Behind the Magazine

As the present editor-in-chief of Citylife (‘I gave myself a promotion!’ she gleefully informed me), Pim continues her father’s legacy of championing causes for the greater good of the city – even if it’s sometimes to the bemusement of the authorities. When a 2012 issue of the magazine was rumoured to have been critical about Chiang Mai’s Tourist Police, it provoked a visit by the police to the Citylife offices.

There, a defiant Pim handed out the copies of the magazine to the police officers, challenging them to read the article and come back if they actually found anything libellous. The police didn’t return. ‘The fact was, they didn’t read English. They had only heard that I was mean about them,’ Pim comments dryly.

Perhaps it’s this tenacity in the face of Thailand’s sometimes heavy-handed authoritarianism that is the reason why, almost two decades after taking over the helm of the company her father founded, Pim and her team at Citylife is still the go-to source for news among this city’s English- speaking community.

With grace, humour and not a slight touch of steely resolve, Pim cuts through the often- vexatious bureaucracy of Thai officialdom to hold the city’s appointed officials accountable to the community they serve. The magazine has grown to become northern Thailand’s most widely-read English-language news and information source, both in print and online. Its popular website has visitors that number in the millions.

Technology, too, has played a part in the continuing success of the company. Under Pim’s direction, the company has also expanded into graphic design, social media marketing and branding for businesses in Chiang Mai as well as other cities in Thailand’s north. The company employs over 20 staff and has hundreds of Thai and international clients. Thanks to one very determined woman, the little newsletter that could has come a long way indeed.

___________________

For more on the latest topics related to business, technology, finance and more, read our digital versions of In Focus magazine, issue 1, issue 2 and issue 3.